Most early tattoo artists were attracted to the ancient craft of tattoo artistry because of a burning desire to express their creative artistic ability. The appeal of freedom of an unencumbered profession. They were their own boss, answering to no one.

They were like a close-knit family drawn together by an unorthodox and vagabond way of life. They all seemed to work with each other at one time or another. Making it hard to know who originated some of the most popular and established tattoo designs. Even though the designs may be attributed to one tattooist. They were friends, adversaries, companions and sometimes worked alone, but never for long. There was camaraderie, jealousy, solidarity and division but they stuck together against all odds, just like a family. The good outweighed the bad. Rewards and returns were worth all the adversities and sacrifices.

In Charles Gibbons’ day, they opened their shops anywhere from eight to eleven in the morning. Work didn’t stop until every customer was taken care of, sometimes without stopping for lunch or dinner. There was little time for any social life.

Most tattoo artists in that era were what you would call white collar workers. They wore two or three-piece suits pressed to the nines; starched white dress shirts; ties or bow-ties, stockings held up by garters, polished patent leather shoes, and stylish Stetson dress hats. Charles Gibbons considered himself a professional business man. He dressed like a professional business man. Modern times have drastically changed the mode of dress in the tattoo community.

A twentieth century tattoo artist’s day consisted in taking care of customers, setting up needles and equipment, inventorying and ordering supplies and sterilizing equipment after each use. The quality of a tattoo not only depended upon the artistic talent, knowledge and expertise of the tattoo artist, but it also depended upon the quality and precision of the tools of the trade he used. A lull in customers provided an opportunity to draw and paint new flash. Then cutting a celluloid stencil for each new design had to be carefully done with a phonograph needle embedded into a wooden dip ink pen handle making sure they didn’t cut too deep so the celluloid wouldn’t crack or etched too shallow. This was so the image transferred the charcoal dust onto the skin clearly and evenly. Modern tattoo artists don’t have to be concerned with that tedious, time consuming task. They also don’t have to be careful not to rub off portions of the black powder image before the entire tattoo is completed. Now they have access to unimaginably sophisticated, life-like computerized images and renderings that were virtually unheard of in Charles Gibbons’ day. Ultraviolet ink that virtually makes a tattoo glow in the dark is also currently available but it is basically frowned upon by reputable tattoo artists, because it has caused allergic reactions. Before leaving in the evening, they sterilized the last equipment used, then cleaned and organized the shop readying it for the next day. The most important and sometimes most difficult task of the entire day was to keep the customers happy. Sometimes an impossible task. No tattoo artist is immune to having to deal with at least one trouble-making customer sometime during their long day. In the end there was nothing more fulfilling and rewarding than to have a satisfied customer and to know you accomplished a job well done.

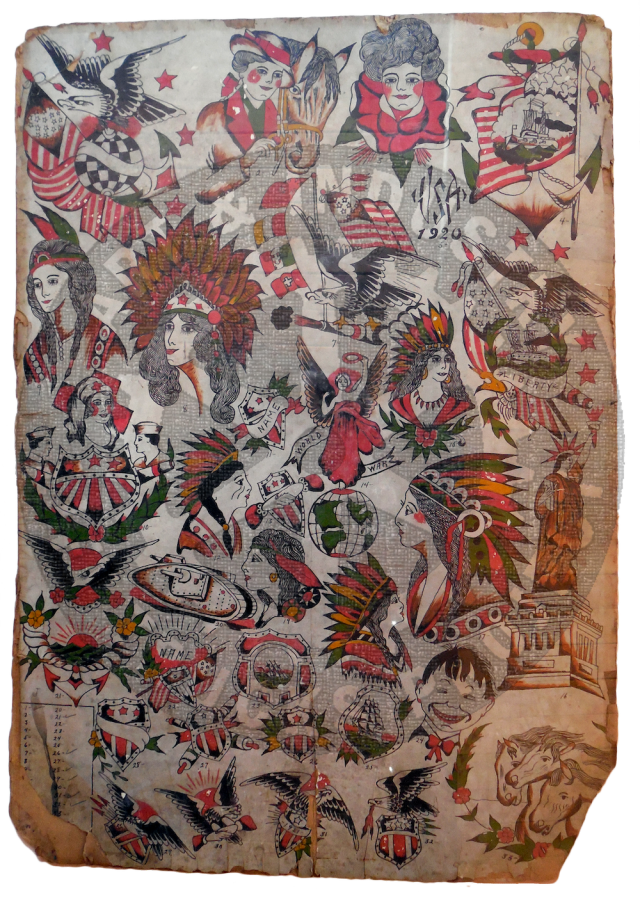

Attributed to Red Gibbons

Attributed to Red Gibbons

Apprenticeship was and still is, the only way to learn this ancient sacred artistry that required long grueling hours and total commitment. Its secrets, techniques, and complexities is not easily learned. It is more difficult to precisely apply them while steadily holding a cumbersome, vibrating apparatus on moving skin with bone and nerve-endings beneath it. There is absolutely no room for mistakes. No erasing here. Armpits, backs, ribs, groin and feet can be extremely sensitive to tattooing. That is probably why Betty Broadbent has no tattooing in any of these areas and very little on her upper back. It didn’t stop Artoria Gibbons, however.

Charles, “Red” Gibbons was a master tattoo artist for over 40 years. He lived from 1879 until1964. A brutal robbery resulted in the loss of one eye. An unfortunate construction accident resulted in the loss of his other eye leaving him totally blind. Nothing else but death could have ended his beloved career as a tattoo artist. He was devastated to the extent of no longer wanting to live. However, with the love and care of his wife and daughter he lived for nearly twenty more years.

The ancient and revered craft of tattoo artistry is constantly evolving. Innovative equipment, techniques, applications and designs are constantly being discovered. Charles Gibbons would be utterly amazed if he could see all the changes in his profession today.

Written by Charlene Anne Gibbons, February 2014

Daughter of Charles “Red” Gibbons, Master Tattoo Artist & “Artoria” Gibbons, one of the most renowned Tattooed Ladies of the twentieth century, tattooed by her husband, Charles Gibbons.

They were married in 1912 in Spokane, WA. Charles was 33 years old & Anna Mae Huseland was 19 years old. She was not tattooed until 1918 and 1919.

A book is presently being written by Charlene Anne Gibbons about the remarkable lives of Charles & Artoria Gibbons.